Rialto Theatre - 4/30 American Master

THE AMERICAN MASTER ORGAN COMPANY LIVES ON

Butte, Montana

Organ installation timeframe: 1917 - 1964

Back to the Rialto Theatre main page

By John Peragallo (as told to Dave Schutt in 1974).

Posted by PIPORG-L Internet mailing list on April 13, 1998 and later published in THEATRE ORGAN, Jul-Aug 1998.

This is the story of an ambitious young organbuilder. He embarked on an

adventure that is just as exciting now as it was when it occurred in 1917.

But that's getting way ahead of the story.

John Peragallo was born in New York City's lower east side. His parents

had come from northern Italy in 1895. By the time he was 12 he was anxious to

get started on a career of his own. At the same time Ernest M. Skinner was

gaining great acclaim for the fine organs he was building. When cathedrals

and churches in New York City wanted the very best of everything, the organ

was an E. M. Skinner. John Peragallo joined Skinner's maintenance crew that

worked under the distinguished guidance of Fred L. Wilck. John learned fast,

and he was soon tuning and regulating reeds in addition to his other

maintenance chores. After five years of this excellent training under a

master craftsman, he was ready for something bigger. Fred Wilck hated to lose

John and regretted that the Skinner Company couldn't offer John a higher-

paying job. However, he didn't wish to hold him back, and therefore he

encouraged John to move to a new organ company that was being formed in the

booming industrial city of Paterson, New Jersey.

Paterson, which is just west of New York City, had a reputation for

aggressively attracting new industries. The president of Paterson's Chamber

of Commerce was James T. Jordan, who was very successful in the piano

manufacturing business. In 1915 he encouraged three enterprising young

musicians to form a company to build organs. There were the two Ely brothers

and Frank White, who later went on to fame as an organist at the Roxy Theater

in New York. They decided to call the company the "American Master Organ

Company." It was capitalized with $50,000. Mr. Jordan was so enthused about

the project that he invested $35,000 from his personal fortune. All that was

lacking was someone who knew how to build organs.

About this time (1915) there was a general exodus of exceptional talent

away from the Wurlitzer organ shops in North Tonawanda, New York. Many, many

fine craftsmen had been drawn to Wurlitzer by Robert Hope-Jones's personal

magnetism. When he died in 1914, many of these people left Wurlitzer. Earle

Beach, J. J. Carruthers, R. P. Elliot, Fred W. Smith, David Marr and J. J.

Colton were in this category.

A fine foreman by the name of MacSpadden was also in this category. He and

some of Marr and Colton's friends in Warsaw, New York, had built a small

organ for a theater in Ottawa, Canada. They were anxious to be on their own.

This team fulfilled the need of the American Master Organ Company. MacSpadden

became the factory superintendent in Paterson, New Jersey. He brought his

blueprints of Hope-Jones's chests with him and blueprints of the magnets,

too.

Other master craftsmen were recruited. Carl Sherman (later with Kimball)

built chests. The new company had its own wood and metal pipe shop under the

direction of Mr. Meyer, who was a cousin of the pipemaker, Jerome B. Meyer.

E. M. Skinner lost Mr. Brockbank, their reed voicer, to the new company.

Our energetic teenager, John Peragallo, stepped into this environment of

extraordinary talent as head of the electrical wiring department. The owners

of the company were locked in arm-to-arm combat with the enormous Wurlitzer

resources, and they had to have something special to offer. The musicians who

controlled the company wanted versatile, well-unified organs. The combination

action and relay/switches were important selling points. Price was also

important. American Master organs sold for about half of their Wurlitzer

equivalents.

During the first two years of operation the company turned out five

theater organs (including the one in Ottawa) and four church organs. The

theater organs had "piano consoles." The top manual was a piano keyboard, and

the pipes were located in cabinets in the orchestra pit. (However the Ottawa

organ chamber was above the proscenium arch.) The church organs had five or

six ranks and two manuals.

Then one day there was great excitement around the American Master Organ

Company. Frank White had bid on a deal with the Silver Bow Amusement Company

of Butte, Montana, that would set a new standard for organbuilding

excellence. It was to be a 30-rank organ with four manuals. Wurlitzer's quote

was $45,000, and the American Master quote was $20,000. If they got the job,

and Frank White was sure they would, it would require the most dedicated

effort from all 35 employees of the American Master Organ Company.

The Silver Bow Amusement Company was building the largest theater ever to

exist in Montana. It had approximately 1,200 seats with a balcony and a

luxurious promenade behind the seats on the main floor. The promenade was

isolated from the auditorium by glass partitions that were beautiful beyond

description. The theater even had an "air-washer" cooling system to keep the

customers comfortable in the summertime. The theater was being built as a

motion picture palace, and the acoustics were intended to enhance musical

presentations from either the pit orchestra or the grand organ that spoke

through a latticework grill in the ceiling. They called the theater the

"Rialto" with the expectation that it would bring Broadway to this remote

mining town.

The organ was patterned after the very finest Wurlitzers of the time.

However there were noticeable improvements everywhere. Extra unification was

provided by John Peragallo's relay that was of monumental proportions. The

sound effects, traps and percussions were extraordinary. The sensational

reiterating cymbal and 32 tuned tympani drums on the pedal were particularly

noteworthy. The console was a model of beauty and convenience. The sound of

the echo organ (including its Vox Humana on 15" wind) was funnelled through a

huge tin duct so that it appeared to come from the rear of the theater. There

was a 32' Diaphone on 25" wind.

There were also some peculiarities: the organ had only three tremulant

stopkeys. It had a roll-top console. The combination action was "blind;" that

is, it didn't actually move the stopkeys when you pushed a combination

piston. A small light came on to indicate which stops had been selected by a

particular piston. It had a 5-rank unenclosed great division. There was a

reed stop called a Kinamoco which had apparently been discovered by Mr.

Brockbank in one of his sober moments. The stopkey engraver preferred to call

the wood harp a "Miramba." The 32' Diaphone consisted of three pipes (CCCC,

DDDD, GGGG) which lay horizontally behind stage and were primarily to form an

exceptionally terrifying thunder effect.

After eight months of work in the factory, the organ was almost ready to

ship to Butte. The Tuba and Diapasons had arrived from Samuel Piece's pipe

shop in Massachusetts. Most of the organ had been assembled and tested in the

erecting room in Paterson. However the vacuum-operated percussions had caused

problems from the beginning, and they still were not working properly.

However the theater was ready for the organ, and the installation had to get

started or the American Master Organ Company would be liable for a $100 per

day penalty that was part of the contract. In March, 1917, the organ left

Paterson for the long trip by rail to Butte, Montana. The percussions were to

be shipped later.

A few days later on March 20, John Peragallo boarded the Nickelplate RR

line to begin almost four months of frustration as the installation foreman.

With him was a helper, Arthur Hughes, who was primarily a brick mason by

trade.

When they arrived in Butte, they were surprised to find that it was a

highly-organized union town. The construction workers who were building the

theater were concerned whether the organ had been built with union labor.

When they saw all the electrical wiring, they were adamant that it should be

connected by union electricians. The rigging into the chambers had to be done

by union ironworkers. John Peragallo told Cy, the union spokesman, that there

wasn't any organbuilder's union, and that his only concern was to get the

organ playing for his company. He also sent a telegram back to Paterson

advising them that they could expect additional expense to hire some union

riggers.

It turned out that Cy respected John Peragallo's ability to assemble the

hodge-podge of seemingly unrelated pieces. They developed an understanding

whereby John used union labor during the day, but after midnight John could

do anything he wanted.

Nearly two months went by, and the theater was about ready to open. The

percussions had just arrived. They never did work right! Their vacuum actions

had been assembled incorrectly and had to be modified on the job. In

addition, the armatures were soldered to phosphor-bronze springs. The few

armatures which had survived the trip from Paterson became unsoldered soon

after the units were placed in operation. On a good day, the electromagnet

winding department in Paterson produced almost as many good magnets as they

did rejects. This nonuniformity of magnets was most noticeable in the

critical vacuum actions for the percussion units.

Time was running out. The thought of the $100 per day penalty clause was

on everyone's mind. Frank White decided to come out from Paterson to see what

was taking so long. He entered the theater demanding to know, "What's all

this (expletive deleted) with the union?" When Cy heard this, he jumped on

Frank, and a good fight got started. They were both big men. John Peragallo

succeeded in stopping the fight by convincing Cy that it was just Frank

White's blustering nature to talk like this.

However Frank White (or anyone) could not perform the miracle that was

necessary to get the organ playing in time for opening night. In fact an

orchestra played the pictures for several weeks while the organ was being

finished. At last it was ready to try. The 20 hp Kinetic blower supplied

plenty of wind for the organ and vacuum for the percussions. The organ

sounded magnificent. Everyone was very pleased. The acoustics of the theater,

coupled with the fine pipework and voicing, produced a sound that was

unforgettable. In fact, the volume of the 32' Diaphones had to be reduced

because the beautiful glass partitions at the rear of the theater shattered

from the vibration. The result lived up to the motto of the American Master

Organ Company: "Science, Musicianship, Craft; Master Workmen to Master

Musician."

In the meantime, Frank White had returned to Paterson because there was

much trouble at the factory. MacSpadden, the factory superintendent, had

quit. The unforeseen expenses of the Butte job combined with the penalty

clause had drained away what little cash was left. If they could get the

three-manual organ delivered to the Central High School in Paterson, they

could collect a large installment of its $10,000 purchase price. Shield

Toutjian was on his way from California to become factory superintendent and

possibly part-owner of the company. He was one brother of a family of

musicians and musical instrument craftsmen from Armenia. Around 1900 his

father, Lucius, had restored ancient musical instruments for John Wanamaker's

"Museum of Arts" in Philadelphia. Lucius and his four sons, Shield, Robert,

Bartan, and Kersam worked for the Los Angeles Art Organ Company and for

Murray M. Harris. But that's another story.

Toutjian finished the factory work for the Central High School organ. But

he could see that the American Master Organ Company was nearly dead. They

didn't have enough money to keep the doors open long enough to ship the

Central High School organ. The Butte organ and poor management had bankrupted

the firm. They wired John Peragallo $71.80 to cover his fare, and told him to

come home; they were bankrupt. So on July 16, 1917, he left Butte--never to

return.

When he arrived in Paterson, he found that the previously thriving little

company had disintegrated. Frank White was playing in a theater and giving

organ lessons. The Ely brothers had taken jobs as accountants in New York

City. Only James T. Jordan, the piano manufacturer, had any interest in the

company. Jordan advanced more money for John Peragallo and Shield Toutjian to

install the Central High School organ. When that was done, Toutjian decided

to become a traveling missionary for his own religious sect. Jordan

encouraged Peragallo to remain in Paterson and continue in the organ

business. Peragallo acquired the logo with the motto and some of the shop

machinery from the American Master Organ Company and founded his own company,

the Peragallo Organ Company, in 1918.

With his son, John, Jr., and his grandsons, John III, Frank and Stephen,

the Peragallo Organ Company is thriving and anticipating a still greater

future dedicated to "Science, Musicianship, Craft; Master Workman to Master

Musician."

What happened to the organ in the Rialto Theater? The manual pipes in the

main chambers were removed years ago, and their whereabouts is unknown to the

writer. Shortly before the theater was torn down in the summer of 1964,

Ronald McDonald purchased the remains of the organ. This included the pipes

from the previously-hidden echo organ and the unenclosed great division. The

console was located in a moving a storage warehouse. It had been there for

about 32 years. McDonald paid the storage bill of $32 and took the console.

There was so little time before the theater was demolished that much of the

organ went down with the building. This included the 32' Diaphones, many 16'

pipes, the grand piano, the huge relay and switches, the blower, and the

entire unenclosed great division.

The console was later sold to Bob Breuer, owner of Arden Pizza and Pipes,

Sacramento, California. Bob had it cleaned up, specially lighted, and

displayed in his pizza restaurant.

The story continues with an account from Ron McDonald who removed the instrument from the theatre in 1964.

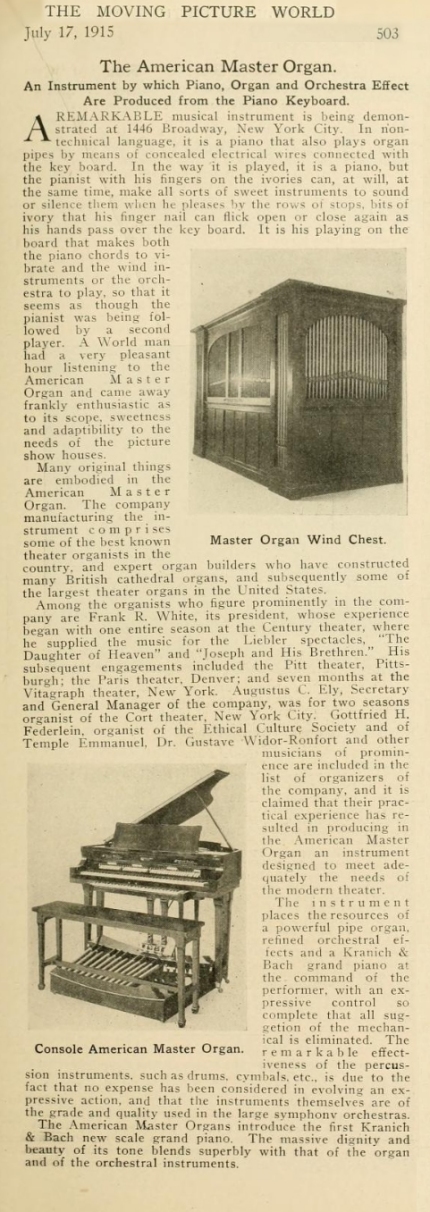

Article from The Moving Picture World, July 17, 1915, p503

About this site © PSTOS, 1998-2020